Bex Massey

Many of your works feature known signs and signifiers from the 90s era. What is it that draws you to this period and it's iconography?

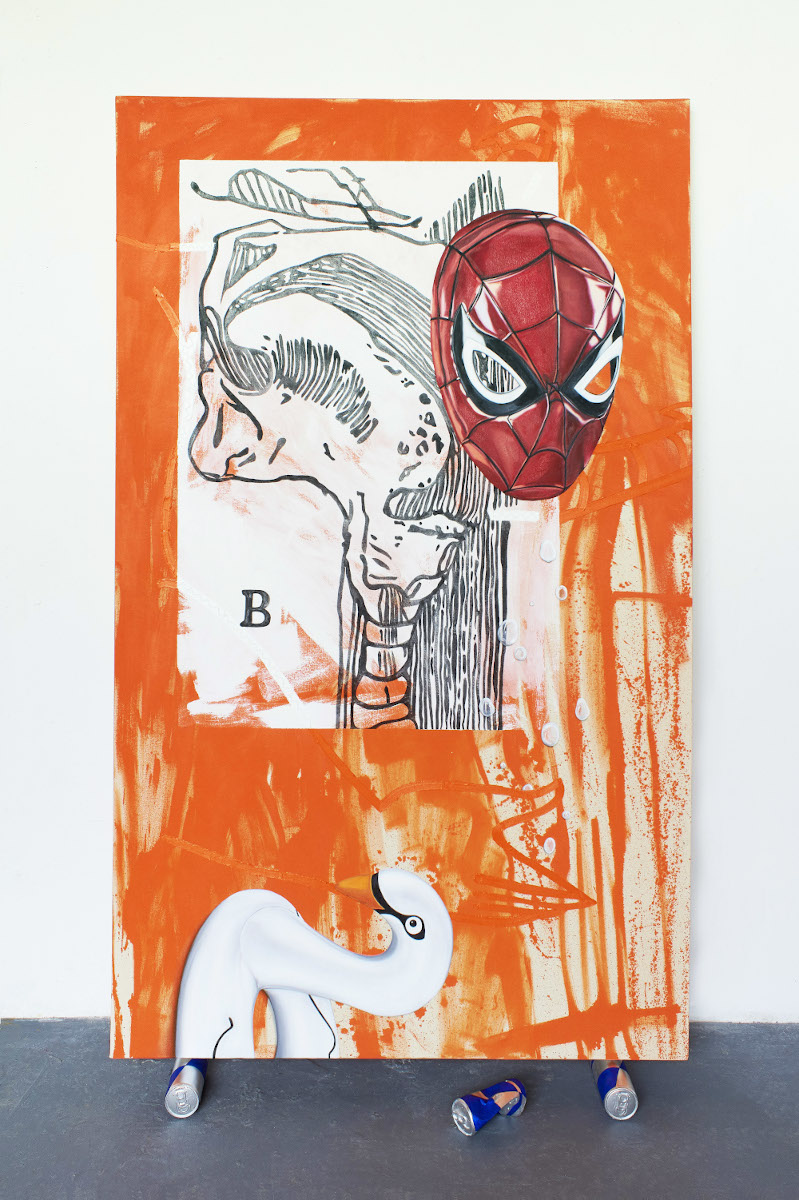

So, I love the 90s: Its smell. Its look. Its feel. It didn’t seem to take itself very seriously. I mean how could it-it was the era that conceived the shell suit? I think that this levity is a great distraction tactic when discussing (often) difficult topics. Who wants to opt into the misconception of ‘angry feminist’ entrenched in our psyche since the 60’s when you can dress up a potentially divisive discussion so that everyone can interact with it rather than just those with a similar agenda to you? Who wants to preach to the choir? For systemic bigotry to be upturned the real agency is talking to everyone and especially those who neither want to listen or think it's time for change.

It’s a bit more than loving a lived consciousness however-I appropriate iconography from the bygone era of my 80’s/90’s childhood as it brings with it a degree of ‘safety’ that I am yet to find in our recent history pre-COVID 19 or ‘new normal’. Since I started using these time-specific signifiers in 2013 (and never more so than now) the world has seemed to be on a rollercoaster to destruction. Daily headlines make us aware of climate, political and social unease and looking at dated packaging and nostalgic prints help soften this. What is more when combined with the feminist issues that I mediate; this appropriated imagery poses an interesting dilemma when we think back to the ideology that ‘girl power’ promised us versus what this third-wave feminism actually delivered. Dress the ugly as beautiful and people will look.

Exploring your work, I get a sense of contrast between the bold colours and cartoon elements against sobering societal topics such as gender and class. Could you dive into that a little for us?

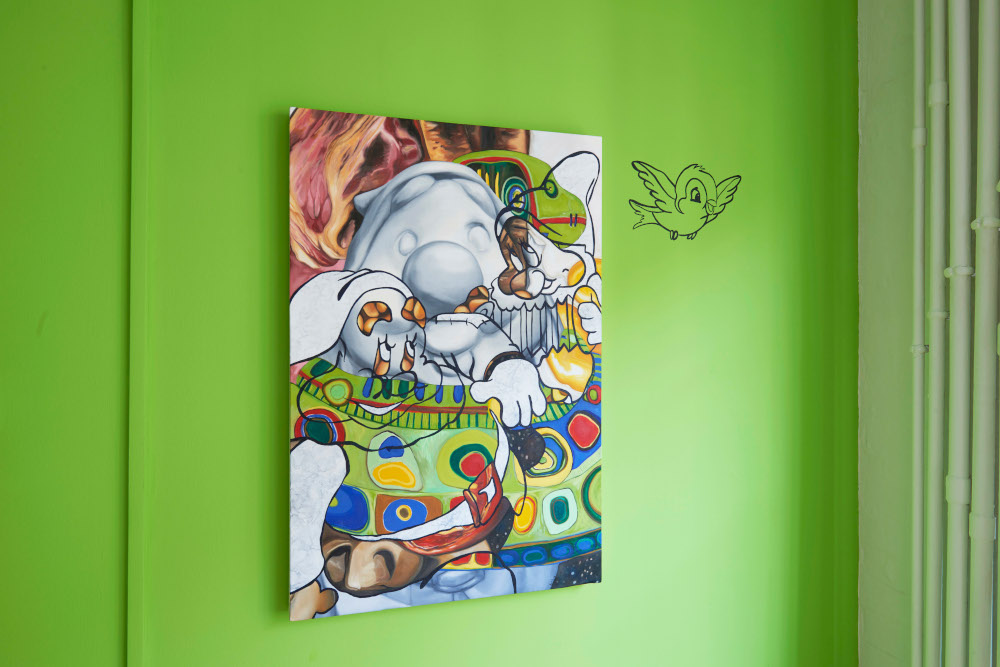

The addition of jovial, recognizable cartoon characters again facilitates a springboard to discuss these heavy ‘societal topics’ -as I touched on earlier- with a lighter approach for the every-person. Cartoons are fleeting and politics conversely feel ever so static (especially at present lest we forget Brexit and the many years it has taken us to ‘no deal’). Cartoons are also often made as a political comment on socio-political events (origins of Marvel versus DC), graphic novels/zines have for time immemorial been designed to continue political messages to the masses and political satire itself incorporates the caricatures of the leads and opposition. This aside I use cartoons and colour firstly because I adore both and secondly to tackle difficult subjects like the divisiveness of class in this country (further subjugated by the inherent North-South divide), LGBTQ+ issues (rolling back of rights across the world and at home) and the 257 years it will take to close the gender gap. These funny, nostalgic and identifiable motifs enable the whole sphere of feminist issues-that is equality for ALL and not just women-to be discussed away from the structured and often complicated term ‘feminism’.

Can you talk through some influences from the art world that have impacted your practice?

Growing up there was a real lack of strong contemporary female faces in art. There was the obvious figurative foursome of Hambling, Emin, Lucas and Saville and although I was a fan of them-they weren’t really concerned with issues/aesthetics that I was. So, I turned to the larger arts bracket and comedy. My most formative memories of the 90’s were therefore the fabulous female triad of standup/actor/writer/program creator Victoria Wood, Jennifer Saunders and Meera Sya. They took satire and used it in the most inspiring manner-to discuss subjects that questioned the status quo and just weren’t being discussed in the mainstream. It is this gift that they brought to British Broadcasting Corporation that informed my artistic voice and the approach I adopt in discussing my subject matter.

David Hockney accompanied me (unfortunately not physically) throughout my practice and before you could even attach the term ‘practice’ to what I was doing. He used to live just around the corner from where my dad was brought up. He is his favourite artist and I readily accepted this torch. Hockney was why I picked up a paintbrush and his innate talent and ability to continually readdress his medium and style is why I continue to do so today. I admire his unconventionality in breaking his ‘brand’, his overt ability and boldness in subject matter and colour and generally just him as a human. In more recent years David Salle, Jim Shaw, Richard Hamilton, Peter Blake, James Rosenquist and Dexter Dalwood have also helped me to better understand layering in paint.

A little later on Heather Phillipson also knocked me sideways: Ever since I walked into her ‘Yes surprising is existence is the post-vegetal cosmorama’ exhibition in 2013 at the BALTIC, Gateshead I have been in awe of her work. I mean she is possibly the best example of an artist dressing up social issues-like climate change-into a palatable format for consumption. And finally, my emerging (some much more buoyant than I) peers influence me daily. The feeling of inclusion and in a sense ‘legitimacy’ that shared ideas, aesthetics or process brings with them is priceless. There are therefore many artists I should thank for this help/support/vision but this would be a long and tedious list so instead I will thank the artists who I feel visually supported by at present (and I hope that your readers will look them all up - if they are not already aware-as they are all BELTA): Sarah Roberts, Katelyn Ledford, Kilee Price, Cherelle Sappleton, Lindsey Mendick, Henry Swanson, Flo Brooks, Joy Labinjo, Fabio Menino and David Rosado. HUGE thanks to you all x

Some of your paintings can be seen to have a layered effect on the imagery they contain, echoing the visuals one might see in popular digital packages like Photoshop. What brought you to this approach in your work?

Without getting too dark (never a good start to a sentence) I worry about our overwhelming reliance on the digital. Having been born pre-mobile (akin to the software we use to date rather than a phone worn as a backpack), computer (laptop equivalent rather than mechanics that fill a room to create one code), interweb and cloud-I understand what life was like pre-digital culture. The relative ‘slowness’ of this time is something which I miss. This new frenetic pace coupled with the many ways in which our data is being taken and often compromised or sold makes me yearn for the past and another reason for delving into imagery from my childhood. In acknowledging this incredible leap in technology, it would be remiss to imagine that the same wouldn’t happen in a further 35 years-so what does that future look like?

Morpheus [The Matrix, 1999] ‘Throughout human history we have been dependent on machines to survive. Fate, it seems is not without a sense of irony’.

This ‘pre-internet’ psyche also pushes me to continuously question the perceived value of the everyday- the hierarchy of image, highbrow versus lowbrow and material worth. I am interested in the manner in which painting brings with it a predestined ‘value’ based on the history of art from which it stems. Women's emancipation is low on a long list of wrongs that need to be rectified and this coupled with the Adobe Suite package-which was expensive from the get go-but at present can only be described as elitist we find ourselves in a triangle of desirability. Then I take this trilateral and I add the exorbitant amount of time it takes me to translate a Photoshop quick link into paint and there you have another layer of ‘worth’. Lest we forget that I am not a computer, I will take longer to commit to an idea as I am not based on algorithms and when I make a mistake I don’t have a ctrl alt delete to rectify them-so here’s another strata of ‘worth’ and so on and so forth.

Moreover, there is something really flippant about the digital era and tasks enabled by software like Adobe Suit are not the only things made quicker. Presidents can throw sexist, racist, homophobic (to name but a few) abuse across continents via twitter at the same speed that ‘deep fakes’ go viral, Snapchat realises and disappears or celebrity Instagram live is aired. My digital mimicry is intended to highlight this notion of speed, intention and accountability.

In your exhibition 'Original Gyal Dem' at Gallery 46 last year, you exhibited a series of site specific paintings which challenged women's glaring omission from recorded history. What was your experience like creating those works and taking part in that show?

Delving into women's history is one of my favourite past times so the research element for ‘Original Gyal Dem’ was fantastic. Painting Jane (Austen), Rosa (Parks), Valentina (Tereshkova) and Indira (Gandhi) was also a dream. As you can imagine there are an infinite number of heroines out there so deciding on just the four women (due to installation space confines) took a while. Also, as female history is just not as readily available as our male counterparts, this ‘digging’ became another time-consuming part of the process. Camouflaged achievements only made this more lengthy-as many female accomplishments have been logged as that of their male colleague or partner. Rosalind Franklin was by no means alone in this burying of truth (Franklins ‘Photo 51’ led to the discovery of DNA double helix for which her male associates James Watson, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins shared the Nobel Prize in 1962).

This being said it shocked me-but really shouldn’t have surprised me-that Women presently occupy around 0.5% of recorded history (study in 2016 by historian Bettany Hughes-so we can but hope that this terrible statistic has improved). So, when the curator Kelly-Anne Davitt asked me to do a site-specific installation for her show ‘The most powerful women in the universe’ if felt patent to me that this statistic should be the premise for the installation. This informed the burying of this tetrad under the gender stereotypes, curb calls, ageism and objectification that had condemned them to ‘the second sex’ and the continuation of these motifs covering the galleries walls as they peeled off and out of the linear constraints of the canvas.

Being in an exhibition with female arts titans like the late Nancy Fout and Nina-Mae Fowler, Kelly-Anne Davitt, Salena Godden, Hanne Jo Kemfor, Clancy Gebler Davies and Sara Pope was a fab. Painting all day with breaks to chat with these fantastic feminist artists or the directors of the gallery really highlighted this as one of my favourite installs. It was also one of those rare occasions where the stars aligned as Gallery 46 isn’t far away from my flat or studio so what could have potentially been an exhausting install was just really fun. Everyone worked very hard on this show and I was incredibly proud to have been part of it.

I get a sense from the last two responses that there is a desire to keep your work accessible to a broad audience. Is that something you feel is important to your practice? Has this changed over time?

I am a firm believer that art is for everyone. This is one of the reasons why I favour art which is multivalent and also try to create varying entry points in my work. I hope that this makes it engaging for ‘art fans’ and ‘non art fans’ alike. I have felt this way since I moved to London to start my BA in the noughties. Even in those early years, I was swiftly aware of the elitist nature of the art world. For example, my soft Geordie twang was quickly replaced with something closer to Queens English (unfortunately this predated the current attitude to a regional accent being ‘en vogue’) in a bid to stop a multitude of small art doors slamming in quick succession. It was this snobbery at a primary level and seeing this disseminate with veracity upwards which pushes me to be as inclusive as possible with my practice. I hope that recognisable imagery, a ‘pop realism’ aesthetic and the jovial nature in which I entwine the two help break down these weird boundaries that have been imposed on fine art. Although I spend a lot of time creating a painting syntax I am not expecting or wanting everyone to get exactly what I am saying. Where’s the fun in that? I am interested in the narratives that viewers create via the coupling of imagery I have selected. If they then want to read or talk about ‘why I made it’, then that’s great but not a necessity.

I get the sense from what you're saying that although imagery in your work may often be grounded in bygone times, there is a direct confrontation of the very real and current issues with technology and its impact on society. Can you share some of your sentiments towards technology as an artist as it permeates further into our lives, including the art world?

I guess some of my reticence towards machines comes from early dystopian movies. The versions including future technology always discuss the manner in which we dehumanise the machine, overwork it, take it for granted and invariably abuse it. Once the computer reaches its next step in evolution it wants revenge and who would blame it? There are already computers that exist which can in theory think for themselves, so how many years do we really imagine it will take for the next step in this evolution? Because I know-namely from the aforementioned sci-fi dramas and indeed the Greeks-once you open this box there is no turning back. I say this with a degree of tongue in cheek but Hannah Fry (world renowned mathematician) outlines many of the pit falls present in the technology we are developing. One of her main cause for concern is the algorithms being manufactured in tech companies today. These are farms for-more often than not-young white cis men to convert code for the mainstream. Some of the most basic code they are creating filters the job market from employee job searches to employer CV selection. If we are only ever a production of our own human experience and in so doing lean in towards what we know-these boys are (probably unwittingly) about to write/writing code which excludes prospective BAME, female, disabled, older, gay etc recruits. This is one very basic example of the code which is being created and is already used throughout the art world. I would question if this already physically nepotistic and now virtually blinkered future looks good?

I am however a realist so stepping away from the ‘Black Mirror’ momentarily I will concede that technology in the arts has its merits: ‘National Theatre Live’ has opened their audience up to people that don’t live in London, are disabled or can’t afford a theatre ticket; Instagram algorithms enable users to browse an infinite amount of art galleries and artists with a touch of the smart phone-not to mention engage in conversation with artists across the globe with a similarly cursory click and who can forget the beauty of Alexander McQueen's spring 1999 finisage? It’s not all bad-it's just not all good!

Lastly, I wanted to touch on something that a lot of artists, including yourself, have been involved with over lockdown which is the Artist Support Pledge. Can you talk a bit about your experience with that initiative and your thoughts around it?

Well here is something which is ALL good! For readers unaware of this fantastic initiative concocted by Matthew Burrows-have a gander on Instagram and use the hashtag #artistsupportpledge (amidst a few unabashed ‘art’ selfies) here you will find art works for sale. Everything is priced at a maximum of £200 plus postage, and once each artist reaches £1000 in sales (or their currency equivalent) they pledge to buy another artists work for £200 and so on and so forth.

I can’t really quantify how much this resource has meant to me during lockdown (and going forwards as most of my shows were cancelled or are still postponed and larger painting sales have been curtailed) as in the space of a week it became my only source of income. Myself and a further one million people who hadn’t completed a full tax year as self-employed slipped through the gap in government aid. I was lucky enough to receive Arts Council England Funding and this combined with ASP gave me hope where there was none-as I regained a means of paying my bills.

My gushy sentiments aside it is also a real leveller of the art market. Without galleries taking a percentage, and due to the nature of community entrenched in the scheme-artists are able to sell works at knockdown prices. This means that art really can be for everyone-as we discussed previously-as it enables EVERYONE to become a collector with works available from as low as £5. Buying into this scheme you are not only supporting an artist physically (and probably to a degree-mentally) but who's to say that you’re not buying into the next ‘big thing’? I am delighted that the scheme is sticking around and I hope it will continue to go from strength to strength. I know a lot of artists-myself included-are relying on its sustainability during these turbulent times.

You can visit Bex's website at https://bexmassey.com/, and follow her Instagram account at https://www.instagram.com/masseybex. The final photo in this interview is credited to Matt Wilkinson.

Published 31 Aug 2020