Charlie Barlow

Your performance and installation works can be seen to incorporate a recurring motif of everyday objects. What is it that draws you to these as a material choice in your practice?

I am drawn to the every day because of its transformative potential; collecting, re-shaping and exaggerating familiar things disrupts normative boundaries within consumer society. What excites me about these objects is their ability to be altered, for their materiality to be realised through cumulative building, for low-value things to take on monumental presence and for passive objects to have a life. I want toilet rolls to become waterlogged monsters, post-it notes to dance away and straws to dribble; new beings that embody and destabilise form and function. Materials chosen have a relationship to identity, order and the environment and are derived from industries including medical, food, stationery, sanitation and beauty - often with gendered importance. Recent work incorporated more found and locally bought materials through assemblage, resonating with the energies of the city. This is an area I plan to explore further in my practice; everyday materials in urban life that have been expelled or reduced to waste as well as eco materials that help to preserve.

There seems to be a tendency to favour using your hands over using instruments to bend objects to your will. Can you talk a bit about this choice in approach to your works?

The hand is hugely important to my creative process – I choose objects that I can playfully pull apart, stretch, tie, layer and mould – I love that proximity to material and the sensory, tactile engagement. Thinking through making is a process I use to discover more about the potential of material transformation and locate ideas; I often work backwards, not knowing what I will make and folding together thoughts – some outcomes escape initial intentions and can take time to realise significance. I reject the common idea that mind is over matter and see the bodily relationship with stuff as an important process. I have also discovered a two-part process; first to alter the material, and the second to arrange, where I find my body is often within a volume of material and the navigation shifts between being close up and afar, from touching to looking from a distance. I think about the ability of play to remould codes of living and put trust in not knowing.

Your installation works strike a careful balance between chaos and order in their composition, but can also often be very intricate and painstaking in their construction. To what extent are these works planned and to what extent to they flow naturally upon production?

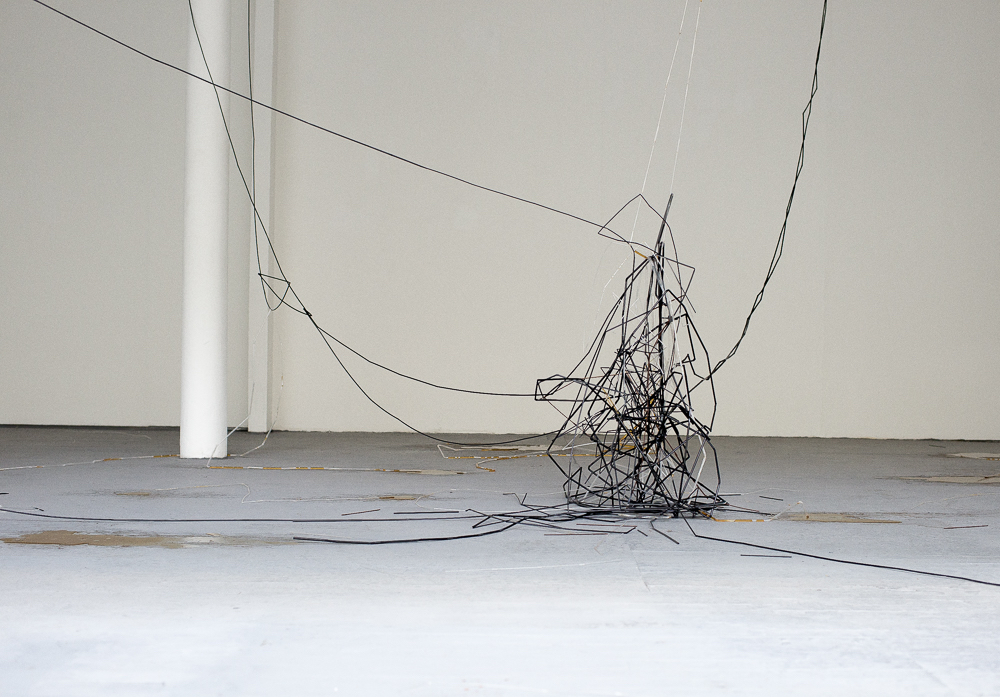

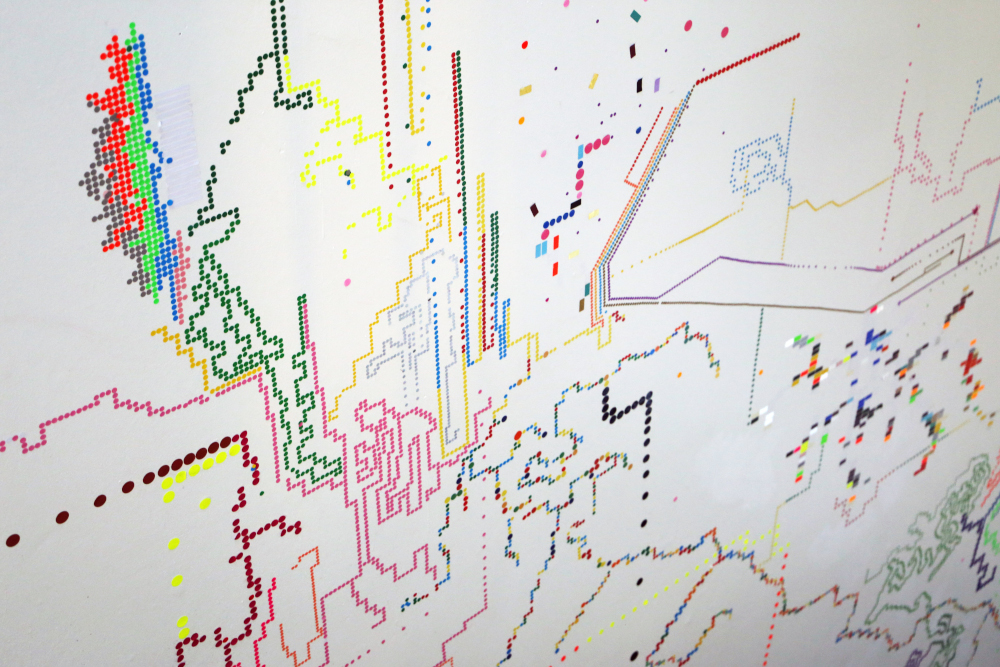

My installation work is largely created through intuition and the composition is gradually realised in the space; I get a feel for the work from smaller experiments and imagine what the form may look like on a larger scale. Once I have found a feel of the material’s new form, sometimes I use this to find related imagery in order to influence and expand associations. I never plan out exactly where things will be placed as it is too deterministic for the work and the ideas that I have inevitably change when the reality of scale and architecture shift the way in which the materials can be expressed. My approach to installation is painterly and I look at the composition from many different angles until I sense a balance between order and chaos – a collapsing of dualisms. Another point of rest is when the work takes on its own autonomy. Works that have a repetitive nature such as Code 2018 place me into a meditative state of flow; I plug into music and lose myself in the making – the intensity of this work embodied an unconscious process in response to the rational logic of the systemising stationary. After discussions, I knew the different floors would change in colour and feel, but I was surprised how the shifts manifested through the guide of my hand; my assistants also strongly added to this sensitivity. To avoid completeness, I like to create a sense of endlessness or have unfinished qualities; I often almost run out of time to finish works exactly how I want to; perhaps it is this reality that prevents completion which is necessary to the energy of the work.

I feel like your work is bold and unapologetic in its uses of colour and materials, can you shed some light on the importance of this with respect to your practice?

I want the colour of the materials to be seen, rather than painted over. Sometimes I incorporate dyes to exaggerate colours in material and expand the palette, but I try to work with the original material colour so that within the transformation there is a relatable, recognisable element. Colour works in different ways dependent upon the works; the graphic red and black palette of the post-it notes in Blank Expression 2018 references Constructivist techniques – and versions have been done in relation to surrounding architecture as well as in support of LGBTQIA+ - this work adapts its purpose to space. For Bogland 2017, the pastel colours tie to innocence and the ‘feminine,’ paired with the intimidating loom of fleshy structures. Different colours of the same object also change the feel of the work, for example, Parched Limbs 2018 is made in both coloured and black straws – one had a childlike feel and the other had the sense of being drunk in a night club. The sensory experience of my work is a really important aspect; the physicality challenges the damage the digital world is having on the relationship we have to the senses and our realities. In contradiction, I use photography to hold the work’s existence post demise, as much a tool for sharing and for remembering. The work likes to disrespect borders so ideas of trespass, rebellion and the uncontained are fitting, as well as the residual traces that often linger.

You were commissioned for Norwich Love Light Festival, exhibiting your work 'Phalanges'. What was that experience like for you?

The exciting part of Love Light Festival 2020 was the development of the light aspect for Phalanges, previously made with white latex gloves. I experimented with glow in the dark paint and found layers of LED light nets had the greatest strength, taking the work to a more mystical place. The public’s engagement with the pair of Phalanges (Yarli Allison and Charlotte Hurst) was intriguing to see, particularly children who were touching the gloves with their hands wondering whether or not they were robots. Outdoors, they were bumped into at traffic lights, jostled in the streets and stumbled across in the dark. I found the timing of the festival gave a new meaning to the gloves; initially, the work was based upon the semi-monstrous hand of commodity desire submerging identity, connecting dirt, danger and hierarchies of the body. Shown a month before the pandemic officially hit the UK, the gloves spoke about the real physical dangers of infection surrounding COVID-19 and types of barriers, protective and destructive amidst socio-economic complexities. The damaged relationship of touch between people during this time is a concern I am continuing to think about.

You mention the importance of urban life in your more recent direction. Was there a driving impetus behind that leaning?

I’ve had a growing interest in the urban environment - the stabilities and precarities, consumptive demands and wastes. My main starting point for gathering materials has been in local supermarkets, go-tos for many people’s essentials. Part of the decision to use everyday items connects to monotonous human habits and questions of what essential can be. Having spent a lot of time in the cleaning aisles, I now want to escape the scent of bleached products to explore materials that have been dispelled from use - those that have a history. Bins are appealing to me at the moment; they are containers that can connect everyone – we’ve all thrown something in the bin and made a choice that an object no longer has value. I’m also interested in the waste that is unrealised, such as scraps on the floor, crumbs down sofas and odd bits in pockets.

Another drive towards the city was undertaking a residency in Hong Kong; here I saw a disco of cultures amongst densely built skyscrapers and green leafy jungle; it made me think a lot about disparities of space and perspective; local and non-local economies, construction, food production, the environment and animals. Some streets were organised by theme such as beads - on one side this was very logical, and the other, excessive and nonsensical. I found that attractive - and sculptural. My experience of the city influenced the choice of materials I developed for the installation Mong Kok 5000; this has encouraged me to follow this approach in other cities in order to form site-specific context.

As of current, I’m also taking note of the control of public space and changes during COVID-19 – particularly one-way systems and identity checks. I have been interested how city design encourages people to walk routes not consciously decided upon as well as and the paths that are regularly left out – now I’m thinking about how walking the wrong way feels, the power of arrows, the relationship people are having to house-bound rules and connectivity.

It'd be great to hear more about that aversion to completion there. Is there a desire to subvert that sort of innate human desire to have things neatly rounded out?

Yes - I think a neat conclusion is a common desire; for me this is uncomfortable. Visually, I find it problematic when my artworks appear too finished – their completeness is held at a point of becoming and unbecoming. Linear concepts that have starts and ends dominate logical order; I prefer ambiguous forms, webbed connections and messy endings (a dyslexic approach). In all of my work, there is a balance between the object’s natural state and my positioning of it. I’m constantly navigating the boundary between freedom and control, leaving things on the brink of growing or unravelling or letting post-it notes fall and bin-bags deflate – time becomes a third medium. This play can also be seen in durational performances, where commitment to a monotonous action can provide a liberational sense of determination, yet also the idea of collapse if I were to continue without limit. I think about external and internal controls, how they have been constructed and how they can be reconstructed without an opposite. The destruction of work also rejects the totality of a classically formed art object, ascribing value to the ephemeral. Transience brings a sense of peace.

You can visit Charlie's website at https://www.charliebarlow.co/ and follow her Instagram account at https://www.instagram.com/charlie__barlow/.

The first image of Charlie in this post was taken by Andi Sapey. The third (Parched Limbs) and fith image (Blank Expression) were taken by Kat Perlak and the sixth image (Phalanges) was taken by Roseanne Cooper.

Published 02 Dec 2020